A Paddler’s Guide to the Seals of Maine

A closer look at the most commonly spotted marine mammal on the Maine coast

If you’ve been on the ocean in Maine, whether by paddle, oars, motor, or sail, you’ve probably spotted at least one seal. But did you know that Maine is home to four different kinds of seals? Some of these blubbery creatures live in our local waters year round, while others are only seasonal visitors. Read on to learn more about Maine’s most beloved marine mammals!

What Makes a Seal a Seal

Seals are pinnipeds – a group of mammals that also includes walruses and sea lions. All of Maine’s seals are members of the True Seal family (Phocidea in latin). True seals are also called earless seals (because of their smooth round heads), or crawling seals, because of the way they scoot themselves flat across the land. This differentiates them from the eared or walking seals (sea lions and fur seals of the Otariidae family) who possess visible ear flaps and waddle with the front of their bodies held upright when on land. When in the water, true seals propel themselves using their hind flippers, while the front flippers are used for steering and stability. The opposite is true of eared seals.

The skeleton of a Harbor Seal

Like other marine mammals, seals breathe air, but spend most of their time in the water. Unlike dolphins, whales, or manatees however, seals are able to come up on land. In fact, they do so regularly to rest, sunbathe, and avoid predators. A colony of seals perched on one of Maine’s numerous rocky ledges is the most common way to view them. Seals eat a wide variety of fish, crustaceans, and shellfish as their primary foods, but have also been known to eat seabirds and other marine mammals on rare occasions. Just like cats and dogs, they are members of the order carnivora, and people are often surprised by how closely their skeletons resemble these distant cousins (since most of their limb bones are hidden inside their blubbery bodies). Their closest relatives within carnivora are the mustelids, such as weasels, otters, minks, ferrets, and skunks.

Juvenile harbor seal, aka a “Sea Dog”!

Harbor Seals

The most common seal in Maine (and the entire world) is the harbor seal. Harbor seals are identified by their small round heads, large eyes, and short snouts. They are often referred to as “sea dogs” or “sea pups” because of their similarity in appearance to a Labrador Retriever and their curious attitude. Harbor seals pup in spring or early summer, then spend the rest of the summer gathered in colonies as the babies grow and put on layers of blubber. In the winter they separate and will live either solitarily or in small family groups. When not basking on rocks, harbor seals are most likely to be seen popping up a few boat lengths behind or beside a paddler, in order to check out those strange-looking crafts. Harbor seals mainly eat fish, crustaceans, and shellfish, and adults reach an average length of five to six feet, weighing anywhere from 150 to 400 lbs. As for coloring, they tend to be a mix of brown and gray, with speckling of different colors and shades, which gives them a thoroughly mottled appearance.

Close up of a grey seal

Gray Seals

The larger of our two year-round pinnipeds, gray seals can be seven to eight feet long and weigh up to 800 lbs! Gray seals pup in January and February, and pups are born with a soft layer of white fur, which they shed after about a month. The winter pupping season means gray seal babies are more mature by the time most boaters are on the water. Gray seals are most easily distinguished from harbor seals by their size and by their longer snouts, which give them a more horse or cow-like appearance. And, they can dive the longest of any Maine’s seal species – able to stay underwater for up to a hour!

For information about recent gray seal pup rescues in Cape Elizabeth, check out MMoME’s facebook page!

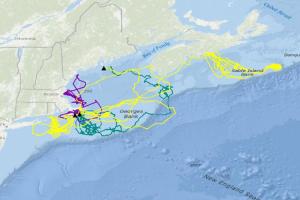

Radio tagging data shows the travels of three different Gray Seals from their place of birth – Map by Kimberly Murray, from NOAA research permit #21719